In this third installment of my musings, I’ll look at a very large (literally) and imposing bit of evidence: ancient stoneworks.

The idea that extraterrestrial visitors are responsible for some of the more dramatic of the Earth’s ancient stone structures has been around for a long time. Its proponents and its detractors have been equally forceful in their arguments. Let’s put all that previous discussion aside and try to look at the concept objectively.

First of all, it’s not impossible that stone age or iron age humans constructed these imposing edifices found all over the world, from Egypt to Central and South America to Southeast Asia to Easter Island. Frankly, though, I consider that explanation highly unlikely. For one thing, how is it that neolithic peoples quite suddenly developed these very impressive abilities to quarry multi-ton blocks of stone, transport them over great distances, and use them to construct enormous and mathematically precise structures? Would you not expect to see early models, with the sophistication increasing with each iteration? And yet, these structures seemed to spring into being overnight, archeologically speaking. It’s as though we suddenly built the space shuttle without ever going through the early phases of propeller and jet aircraft development.

Even more puzzling, why did this ability just as suddenly vanish, even though people still lived where the things were built? In some cases, it was the same people. Structures built afterward, if they exist at all, are stunningly primitive in comparison. Pyramids built in Egypt after the great pyramids were small and shoddy, as though the builders were desperately trying to copy what their supposed forefathers had built.

I have never seen an adequate explanation for this.

And then, of course, there is the amazing precision and sophistication of these structures. It is not entirely certain that we could build some of these things today, with the most modern tools and techniques.

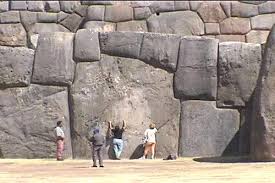

I will restrict myself to discussing just two specific examples, though there are many from which to choose. First, because I have been there, let’s look at the fortress of Sacsayhuaman, near Cuzco, Peru. These impressive walls are composed of granite stones, some weighing up to 200 tons, and many of them fit together so precisely that you cannot slip a butter knife — or even a piece of paper — between them. Take a look:

The fortress and the city it once encompassed were (apparently) built by the pre-Inca Killke culture, about which little is known. I am dubious. Even with today’s precision tools and lasers, it would not be a simple task to re-create this structure. There’s another troubling aspect. As long as you had to painstakingly carve out granite blocks from a quarry, why not carve them all square? It would be so much easier to build a wall this way. Instead, the structure is built like a jigsaw puzzle. It is very difficult for me to accept that a primitive culture using stone tools carved these massive blocks to fit together so closely in such a dizzying array of shapes.

We are also expected to believe that the blocks were lowered into place by raising them on logs and them removing the logs one at a time. How does one do this in such a fashion that the block slips perfectly into place, married to the blocks on either side, all of which were carved separately, and so perfectly that a piece of paper won’t slip between them? Frankly, I don’t buy it.

Sacsayhuaman is far from being the only anomaly in this part of the world. There are unexplained megalithic structures in Bolivia, as well as the well known ruins in Mexico and Central America. The ancient and mathematically precise city of Teotihuacan near Mexico City is particularly mysterious. Even the Aztecs didn’t know who built it; it was abandoned long before they arrived on the scene.

However, now I want to turn to the other side of the world and what is probably the best known and most contentious ancient structure: the Great Pyramid at Giza.

The three major pyramids on the Giza plateau are the Pyramid of Khufu (the Great Pyramid), the Pyramid of Khafre, and the smaller Pyramid of Menkaure. All are named for the pharaohs for whom they were supposedly built as tombs between 4500 and 5000 years ago.

The problem is, they were actually built around 12,000 years ago. Evidence for this comes from the pattern of erosion on the Sphinx, which was built at about the same time. The erosion pattern on the limestone could only be caused by water, but rainfall in this area of Egypt is about the same today as it was 5000 years ago. That is, it’s not common. The periodic but rare downpours the area receives would not have been enough to produce the erosion we see. However, between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago, the area was much wetter, with plenty of rainfall.

Then there is the matter of the pyramids’ construction. There have been a lot of theories put forth in an attempt to explain how it was done, none of them very satisfactory. One recent theory proposes that the Egyptians didn’t carve and move the limestone blocks but instead created a limestone slurry that they then poured into molds to create the blocks forming the pyramids. This theory does not take into account the white cement between the blocks (totally unnecessary if the blocks were poured) or the existence of quarries. Nor does it explain how they got the slurry to the top.

The most common theory is that the Egyptians built ramps upon which they could roll the blocks on timbers up to the the pyramid level where they were needed. The problem with this theory is that the ramps would have had to be as massive an engineering undertaking as the pyramids themselves, and there is no trace of any such constructions.

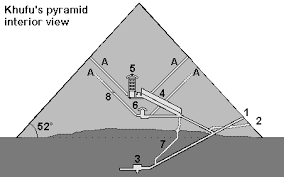

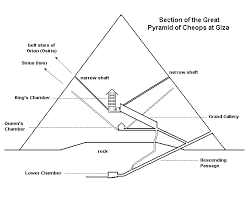

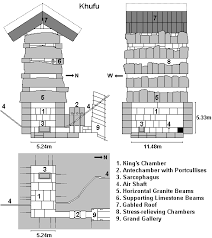

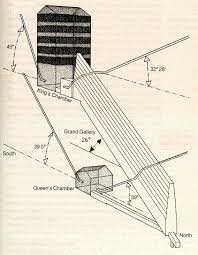

To my mind, though, the biggest mystery is the interior construction of the Pyramid of Khufu (also called the Pyramid of Cheops). An awful lot has been written about this subject, so I won’t go into it here in depth, but it’s worth looking into because the mysteries are numerous (such as how and why the massive granite slabs were carefully put into place above the so-called “King’s Chamber” or why that same chamber shows signs of intense heat). Instead, just take a look at the internal structure:

Put aside all preconceptions, everything you’ve heard or read about this pyramid and just look at it. Here’s a closer look at the “King’s Chamber”:

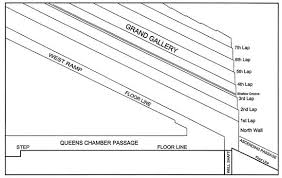

And the “Grand Gallery”:

If you look at all this, it becomes very clear that this structure was never meant to be a tomb. There are no hieroglyphics extolling the virtues of the king who was supposed to be buried there. In fact, there are no hieroglyphics at all. Khufu’s name appears only once, as only as a bit of graffiti etched onto an obscure wall well after grave robbers had broken in. And those grave robbers never found anything: no bodies, no treasures, nothing. The chambers were empty.

The passageways have low ceilings and are uncomfortable to navigate. They were clearly never meant for humans to use. The Grand Gallery is tall enough, but it’s absurdly tall, and like the ascending and descending passageways, the slope is too steep to comfortably walk, either on the two narrow ledges on either side or the recessed center. That’s why steps and rails have been installed for tourists.

The builders would have had to dig the subterranean chamber before construction began, but then why leave it unfinished? They would have had to put all the interior structures in place as the pyramid was being built, but if you’re going to do that, why not make it sensible and navigable? If you’re going to have to carry in bodies and afterlife treasures, why make it so you have to climb up (or down) a 26 degree slope, bent over at the waist, and squeeze through a small opening at the end? And what on Earth is the purpose for those heavy granite slabs cantilevered against each other in layers above the “King’s Chamber?” What purpose could the Grand Gallery possibly serve if the whole structure is simply a tomb?

There are many, many other things about the Great Pyramid that don’t make sense. There is plenty of information on the web and in the many books written about the subject. Graham Hancock’s “Fingerprints of the Gods” is a good place to start. The bottom line is, it makes as much sense to call the pyramid a tomb as it does to say it was built to store grain.

But if the pyramid was never meant to be a tomb, then what was its purpose? Your guess is as good as mine. All I can say is, when I look at the bizarre design of the interior, it doesn’t look like something humans would build. It just doesn’t make sense from a human perspective. It is nothing like anything else ever built, anywhere, anytime. Frankly, it just looks alien.